Book review - Ants: A Visual Guide by Heather Campbell and Benjamin Blanchard

Andy Karran

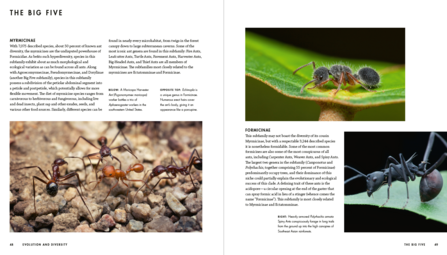

All too often, visually superb books like this fall down when it comes to content but not in this case. This is not just a pretty addition to the coffee table, far from it, the text is readable, detailed and fascinating, both Heather Campbell and Benjamin Blanchard, the authors, hold doctorates (in ecological entomology and evolutionary biology respectively) and the text does not skip on the science, delving into, for example, the ‘discovery-dominance’ theory of niche partitioning in ants and the social and health benefits of exchanging bodily fluids through the process of trophallaxis.

One of my favourite passages and one which exemplifies the science-based but accessible writing style, describes the principles of sex determination and eusociality in ants. For people new to the social insects, the self-sacrificial and apparently altruistic behaviour of workers in a colony is often confusing and its genetic explanations can be mind-boggling. Entire books have been written on this subject but here the authors summarise these complex issues very neatly and succinctly in a just a couple of pages.

The structure of the book is rather unusual but effective. The six chapters are in themselves pretty much as you might expect covering: ant physiology and anatomy ‘What is an ant?’, evolution, life history, behaviour, ecology and ‘Ants and People’, but instead of a seventh chapter cataloguing the amazing diversity of the ants of the world, each of the six chapters closes with a series of ‘Ant Profiles’, each comprising a one page summary of a single genus of ants, discussing the ecological, physiological or behavioural idiosyncrasies of the genus along with details of the global distribution, habitats, nests, diet and so on.

There are seven of these genus profiles at the end of each chapter so 42 in all, representing a very comprehensive sample of the 21 recognised subfamiles of ants. All of the famous ants are there: Eciton, the army ants, with their all-consuming foraging raids across the rainforest floor; Atta, the leaf-cutters with their fungus farms; Paraponera, the bullet ant, so named for the agony caused by its sting which is comparable to being shot; but it was news to me that there are jumping ants (Harpegnathos), weaver ants (Oecophylla) and even dracula ants (Stigmatomma).

If I have a criticism, and it is largely a personal one because it is my favourite subject, I would have liked to have seen more space given to the importance of ants as components of ecosystems and to their genuine claim to the somewhat overused accolade ‘ecosystem engineers’. Most of the ecology in the book is devoted to the extraordinary social, physiological and behavioural adaptations of ants to the world around them and these are fascinating, but the ecosystem functions that ants perform, such as cycling nutrients and structuring soils, is to my mind equally fascinating and could perhaps have been given more attention. But as I say, I am making this a bit personal, a book that covered every aspect of the lives of these wonderful little creatures would need to be thousands of pages long.

If you think you’d like to dip into the world of ants and want some stunning photography into the bargain, or if you know a teenager who you want to inspire with some amazing natural science, fascinating facts and “woah!” photos, my advice would be to look no further.

Rick Mundy, June 2023