Macroinvertebrates

Aquatic macroinvertebrates, such as stonefly, caddisfly and mayfly larvae, live in riverbed sediments and play a crucial role in the riverine food web. Many macroinvertebrates are sensitive to sudden changes in flow and water quality, especially when that is outside the normal range of their habitat. For example, during extreme flood events, fast and turbulent water can scour the riverbed essentially "washing" macroinvertebrates downstream, while shifting cobbles and boulders crush vulnerable individuals. This is known to dramatically impact the abundance and diversity of macroinvertebrates.

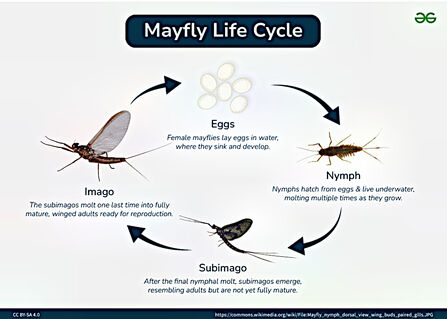

The timing of flooding is crucial for understanding the rate of macroinvertebrate recovery, as many species have highly seasonal mating pattern, with juvenile larvae developing over winter and emerging to mate and lay eggs in the spring and summer. As a result, the timing of the recent November flooding suggests we may see a slow recovery rate of macroinvertebrate abundances and fewer emerging macroinvertebrates in 2026 and possibly 2027. Reduced macroinvertebrate abundance and diversity will have ripple effects throughout the food web, affecting the availability of prey for fish (e.g. trout, salmon, grayling), birds (e.g. dippers, kingfishers) and mammals (e.g. Otters and Bats).